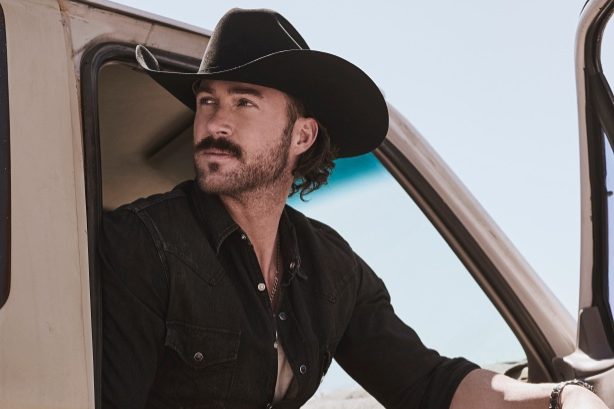

Interview: Rodney Crowell – The Long Distance Run

From struggling songwriter to country superstar to veteran outsider, Rodney Crowell has followed his muse on a 45 year journey that has finally led him to a place where he feels like he’s doing his best work.

Of the 700,000 people living in Nashville in 1972, probably a good 7,000 were songwriters, most of them looking for a break. So, when a 22-year old kid from Crosby, Texas, named Rodney Crowell made it 7,001, no one took much notice.

Crowell believed that he was hitting Music City with his ticket already stamped. “I came to town thinking I had a record deal and the opening slot on a Kenny Rogers and First Edition tour,” he tells Country Music. “None of which turned out to be true. That’s a long story.

So, in the beginning, I was sleepwalking. As I started to wake up to the songwriting thing inside myself, the ambition wasn’t anything but to write a song good enough that Guy Clark or Townes Van Zandt would think was okay. They were already there, close to the street. I had access to a gathering of songwriters at a house on Acklen Avenue that I shared with Richard Dobbs and a guy named Skinny Dennis. So I was getting educated.”

Eight months later, Crowell caught his first break, courtesy of guitar picker extraordinaire and country star Jerry Reed. “Jerry and his manager heard a song I wrote and played at a happy hour at the Jolly Ox, and they recorded it the next morning,” Crowell recalls with a smile. “Jerry paid me 100 dollars a week to write songs in 1973. That’s all I needed. I could keep a roof over my head, and have something to eat, and spend all my time writing.

He had a studio and an office where I would go to hang around. I would just watch him and Chet Atkins show each other guitar licks. Chet was there all the time, along with the likes of Paul Yandell, Buddy Spicher and Vassar Clements. I was a kid and I’d just sit quietly and observe all these incredible musicians. That was a gift.

“I remember when I went to the studio to teach the first song to Jerry and the musicians,” Crowell continues, “I walk in and there was nobody there but Chet Atkins. I sat with Chet for 20 minutes while he explained the console to me. He said, ‘Did you write this song we’re recording?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ What I wanted to do was sneak out and find a pay phone and call everybody I knew!”

Drink Your Fill & Blow U All Away

A lot of the romance and wonder of Crowell’s early days is lovingly documented on the walls of his home studio in Franklin, Tennessee, where we meet for our conversation on an unseasonably warm February day. There’s one photo of Rodney’s daughter Caitlin at 11 months, sitting on the lap of her grandfather Johnny Cash, and a wedding day snap with Rosanne Cash.

Another photograph shows Rodney in 1977 with Hot Band drummer John Ware, at the Rembrandt Museum, and there is also a beautiful vintage poster of the Ryman Auditorium.

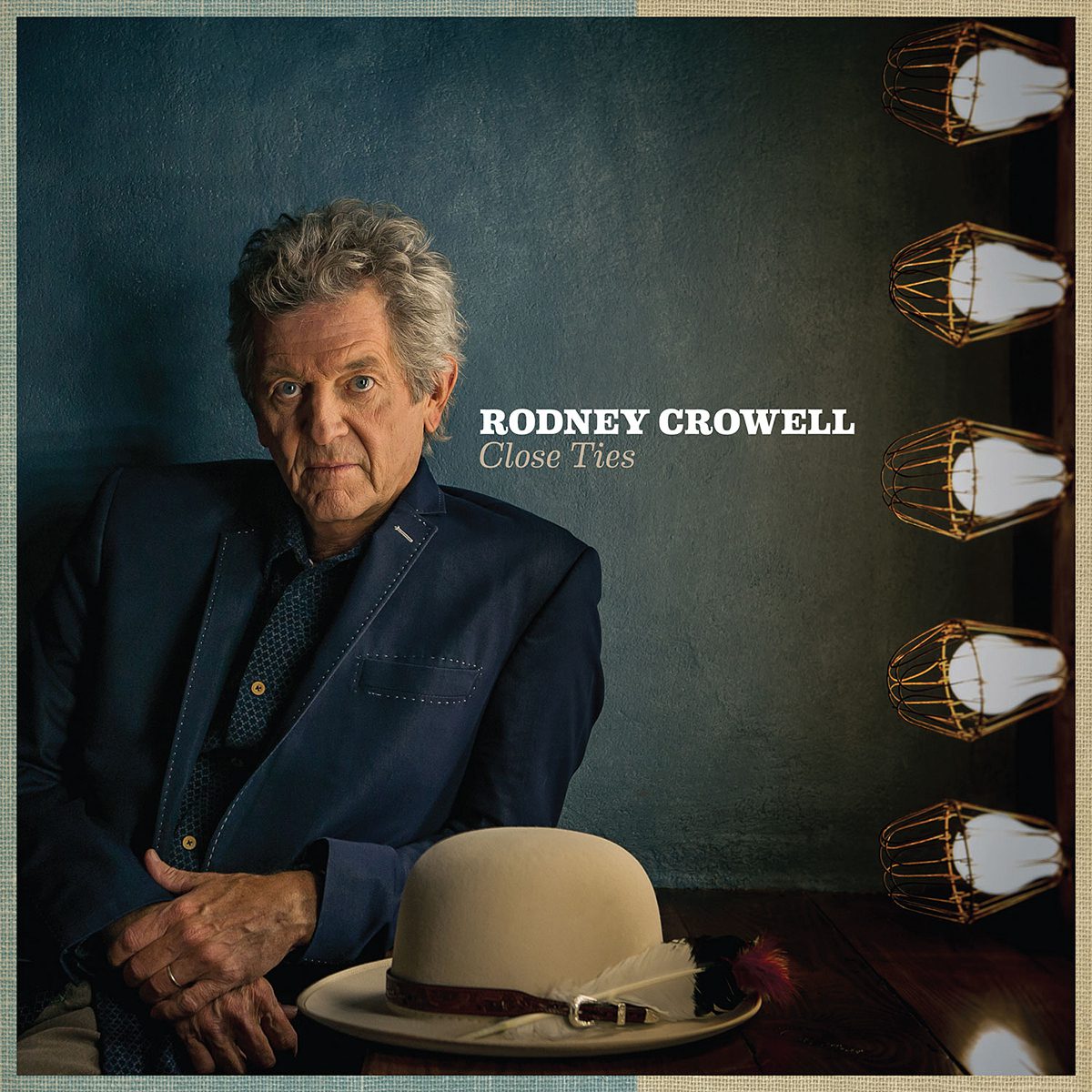

His storied history also finds its way into many of the songs on his latest album Close Ties, especially Nashville 1972, I Don’t Care Anymore and the poignant Life Without Susanna. The latter is about Susanna Clark, one of the most important women in Crowell’s creative life. He says: “Susanna was a muse – a poet, and a really great songwriter and painter. She embodied the goddess as artist.

So, Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clarke, Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Steve Earle, Richard Leigh, Dick Feller and myself all, in one way or another, played to Susanna as an audience of one.

Townes probably came closer than any of us to dreaming those songs the way that Susanna would receive them. Your songs had to be really poetic for her to receive them. She really saw it as poetry. Whenever she received a song that I had written kindly, there had to be some truth to it and it had to resonate as poetry.”

Emmy the Great

By the mid-’70s, Crowell was making more connections.He was invited to join Emmylou Harris’ famous Hot Band, playing rhythm guitar alongside Albert Lee, Glen D. Hardin and John Ware. He also became one of Harris’ favourite songwriters, with her cutting definitive versions of early Crowell classics like Bluebird Wine and Till I Gain Control Again. “Emmylou started recording my songs and shortly thereafter, a lot of other people did, too,” says Crowell.

“People were listening to Emmy’s records and then saying, ‘Well, who’s this guy writing this stuff?’ – Emmy changed my life.”

A hidden gem that Crowell wrote for Harris in 1979 was Here We Are, a duet she recorded with George Jones. With its spare, direct language and elegant melody, it seems a world away from the more dense lyrical songs he’s writing today. But it illustrates his influences and the depth of his songwriting toolbox. Crowell says: “I cut my teeth on Hank Williams, and that kind of very simple language.

That was back in the day when all of these things were new. Hank was writing ‘Your cheatin’ heart will tell on you…’ which is still a great line, no matter what time in the existence of mankind. “It was so very simple, and those very simple, almost Hallmark card sentiments were so new then that it was a primer for how to do it. Then The Beatles came along and scrambled it up.

Then Bob Dylan introduced Rimbaud to songwriting. Suddenly the paradigm had shifted into this broader verbiage. To write with that kind of simplicity became harder because it had been done so well.

“I wrote Here We Are with a purpose. I was having an extra-marital affair during my first marriage and it was kind of about that. It was easy to write, like an old country song. But easy because I had lived in and around Hank Williams, and that music, from almost day one.

It’s really not easy to write that simply. You break down Felice and Boudleaux Bryant’s songs – and the way those melodies are, to try to dangle much metaphor on Bye Bye Love or Love Hurts or any of those songs, it doesn’t work. Joe Cocker once called those songs ‘teen country.’

The funny thing about those simple songs is that they’re really broad stroke. Love songs and ‘man and woman stuff’ are always going to be broad stroke.” As his profile rose as a songwriter, he landed country cuts by Waylon Jennings, The Oak Ridge Boys and Johnny Cash. But one of his biggest – and most enduring – hits came in 1981, when Bob Seger took Shame On The Moon into the pop charts.

All these years later, Crowell confesses that the song has never felt finished. “I’ve been rewriting that song for 30 odd years,” he says with a smile. “I always thought the last verse was dookie. I don’t know why I recorded it, but I did.

Maybe subconsciously I recorded it so it would get covered and I’d make some money. But I’ve recently re-written the whole song. It’s well within my rights to do another version of a song that I didn’t think was right in the beginning.

It’s ironic that that thing was five weeks at No. 2, right behind Beat It, or one of those Michael Jackson songs, and the whole time I’m cringing at the last verse. But I asked Bob Seger about that last verse and he said he liked it – it is all subjective.”

Diamonds & Dirt

In 1978, Crowell signed his own solo artist deal, but it would be a full decade and four albums before he found success. It happened when Diamonds & Dirt set a country album chart record with five consecutive No. 1 singles, including She’s Crazy For Leavin’, After All This Time and It’s Such A Small World, a duet with his wife, Rosanne Cash.

“It was my 15 minutes of stardom,” Crowell recalls. “I just made a good record that happened to catch on. Hand over my heart, it wasn’t by design. I didn’t know I was making five No. 1 singles in a row. It was just paint by numbers.”

Among the No. 1 hits from Diamonds & Dirt was a cover of Harlan Howard’s Above And Beyond, originally a 1960 smash for Buck Owens. So impressed was Howard, the dean of all Nashville songwriters, that he sought out Crowell for collaboration. “As soon as Harlan heard a couple of my songs, he called and said, ‘Hey there, Juvenile, I want you to come on over to the house,’” Crowell says, with a laugh.

“You’d go over and have dinner, then the hook was set, and the next thing you know you’re back over there writing songs. I think he was amused by me. We wrote one song together, Somewhere Tonight, and it was a No. 1 for Highway 101.

Then Harlan said, ‘Okay, Juvenile, we’ve gotta write another song.’ He called everybody “Juvenile.” I said, ‘No.’ He responded, ‘What do you mean no?’ ‘We’ve collaborated twice and both times we went to number one’, I explained, ‘I’m not gonna risk breaking our run.’ He laughed and said, ‘You son of a bitch, I don’t know anyone who ever said that to me’.”

Flirting With Fame

All the attention and chart-topping was exciting, but Crowell eventually started to feel hemmed in creatively and personally by the star-making machinery.

“What I didn’t want was the self-consciousness that was developing,” he says. “In fairness, it’s difficult when you start flirting with fame. My father-in-law

at the time was a famous man, so I saw fame and I saw how well, and not so well, Johnny Cash handled fame.

But for me, I had this very clear vision when I would walk into a room that people would go, ‘Oh, there’s that guy’.

I understood and started to construct a model of myself that was based on their projections. Somehow, knock wood, I realised for myself that to buy into that and become a caricature and try to make art based on that false self-identity was a recipe for disaster.

I know now with enough hindsight that I started to sub-consciously sabotage that. I just knew that if I stayed with that, I’d become a parody of a pose. And I was posing. I didn’t want to pose, so I dismantled it. You have to go around to the radio stations, at like eight o’clock in the morning with all the perky people selling advertising, and I would walk in all sullen and in a bad mood.

I was only interested in the gig later on that night. It wasn’t working and I made their job harder. “In fairness to myself, and them, I needed to get out of there, because I didn’t have the makeup to put on that false pretence. I tried for a while, but it just didn’t work.”

And did Johnny Cash give his new son-in-law any advice on how to cope with these pressures? “No, Johnny wasn’t an advice-giver,” Crowell says. “He was straight-up. He was a big kid, who liked to laugh and joke around. Here was this larger than life man in black, with all that swagger. But away from that image,

he was funny, a cut-up.”

Nashville doesn’t always take kindly to those who refuse to, as Crowell puts it, “play the game,” and he watched his star fall quickly out of favour. At least on radio and in the industry.

His Master’s Voice

For many, Rodney evolved into a kind of beloved outsider, always chasing his own muse, however far it took him away from commercial success.

His songs continued to be turned into hits for others – Making Memories Of Us for Keith Urban, Please Remember Me for Tim McGraw and Ashes By Now for Lee Ann Womack.

It wasn’t until he released 2001’s The Houston Kid album that Crowell said he really started to find the voice he always wanted as an artist.

“It wasn’t about changing my approach to singing,” he explains.

“It was more the blockage inside, the pathway, the delivery mechanism. Psychological blocks that would tighten and constrict the vocal cords. But then, as I’ve said, my voice just needed about 50 years to get to the right place to deliver the quality of language that I had been writing. I’m unapologetic.

I was delivering good language in my early 20s, with songs like Till I Gain Control Again and Ain’t Living Long Like This. But for my money, I didn’t have the vocal apparatus to deliver language and melody of that quality. I got by. I got a record deal and made some records, but I knew. People say, ‘You continue to get better’. One real reason for that is that at age 50, when I made The Houston Kid, vocally it started to work.

I was inspired by that. I’ve been keen to work and make art since then, because I think, finally I’ve got the ingredients I need. “It’s funny, my more commercial period in the career was before. But in this new century, I tell my kids, that’s where my legacy starts. They laugh about it, but I really feel that way.”

As he gears up to tour Close Ties, Crowell says that he doesn’t feel obligated to recreate the arrangements on the album. “Really, I want to do an acoustic show,” he says. “I’ve got dates on the books, but I’m trying to figure out how to do something interesting. Maybe a different combination of instruments. I’d given some thought to a Celtic harp player. Some interesting colour.

I never subscribe to the notion that we have to go out and play the songs the way they’re recorded. We might take some hooks from those songs. But it’s a new day, a new group of musicians. Let’s play these songs as we are. I haven’t quite solved the riddle of that yet, but I’m getting closer.”

At the interview’s end, Crowell signs a copy of his autobiography Chinaberry Sidewalks for me. We’re talking about the mysterious business of words, whether straight prose or song lyrics, and Crowell smiles. “It’s a good way to make a living, isn’t it?,” he says.

“But honestly, I don’t find songwriting to get any easier, necessarily. You get older, time flies by, and I believe that inspiration only comes to an artist of certain years if the dedication and passion is still there.

“Before I leave this world, if I can create something that’s timeless and museum quality, then it will have all been worth it. And if I don’t? It still would’ve been worth it.”