Interview: Alison Krauss – Gal Power

Four years in the making, Alison Krauss’s first solo album in 18 years – Windy City – was anything but plain sailing. But, as the bluegrass star tells Paul Dimery, she overcame the turbulence to emerge triumphant.

Alison Krauss sounds a bit fed up. An afternoon of phone interviews has left her hoarse and exhausted, and now she’s struggling with my British brogue and a transatlantic phone line that insists on cutting out every few minutes, leaving both of us hanging in mid-air.

After exchanging niceties, I begin our interview proper by asking for a personal recollection of her formative years, before she rose to fame as one of the world’s biggest country stars and began collecting Grammy Awards for fun (she has 27 to date, making her the most prolific living recipient along with Quincy Jones, a man 38 years her senior).

There’s a long pause at the other end of the phone as she casts her mind back through her career. A very long pause. Then a crackle. Nope, the line has gone dead again.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Originally, Country Music was set to meet the Illinois-born bluegrass sensation in person, in London, prior to an intimate gig at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios where she would showcase her new album, Windy City. But a throat infection meant that Krauss had to cancel her visit to the UK at the last minute, and so here we are, trying to overcome tiredness and technology on either side of the Pond.

No wonder she’s feeling frustrated. “I’m still not completely over [the illness],” she rasps when the connection finally remedies itself. “It was only supposed to last about three weeks, but it’s not letting go.”

Early virtuosity

Her downbeat nature today jars with those oft-recounted tales of the wildly talented ingénue who entered her first fiddle contests aged eight, laying waste to her rivals with thrillingly offbeat renditions of The Beatles and Bad Company; formed her first band at 10; and discovered bluegrass music at the tender age of 12, taking a shine to banjo stalwarts Ralph Stanley and J.D. Crowe while her school mates were listening to Cyndi Lauper.

When the Society For The Preservation Of Bluegrass in America labelled Krauss the ‘Most Promising Fiddler in the Midwest’, and Vanity Fair magazine followed suit by describing her as a “virtuoso”, she’d not yet reached her 14th birthday. “I would just show up and do my thing,” says Krauss, recalling those early competitions with a modesty that belies her lofty achievements.

“I don’t remember being goofy or nervous about doing them at all, and I think that might’ve been irritating to my folks. They felt like I should be taking things a bit more seriously or realise what was going on, but I don’t remember being terribly aware.”

It was Krauss’s mother, Louise, who’d first set young Alison on her path to musical destiny, encouraging her daughter to learn the classical violin at the age of five.

But Alison soon gave that up to pursue what she deemed to be her true calling in life: “I liked fiddle music a lot,” she explains. “I would spend hours cassette-recording the famous fiddle players and learning the tunes that other people did. I studied how they held their bow and tapped their feet, that kind of thing.”

She proved to be a natural; indeed, such was her skill with the instrument that she quickly found herself in demand among seasoned artists looking for session talent. One of those, bassist and songwriter John Pennell, was so impressed with this fresh-faced starlet, he invited her to join his band Silver Rail (later to become Union Station).

It proved to be a match made in heaven; Krauss’ energetic performances with the group helped to earn her a deal with Rounder Records – putting her on the same label as one of her childhood heroes, J.D. Crowe – and while Pennell eventually drifted away from the line-up, his protégé has recorded and toured with them prolifically ever since.

In fact, we’ve become so used to Krauss performing with Union Station, it came as something of a surprise to learn that, though certain members of the band make cameo appearances on the recording, Windy City is officially a solo venture – Alison’s first since 1999’s underrated Forget About It.

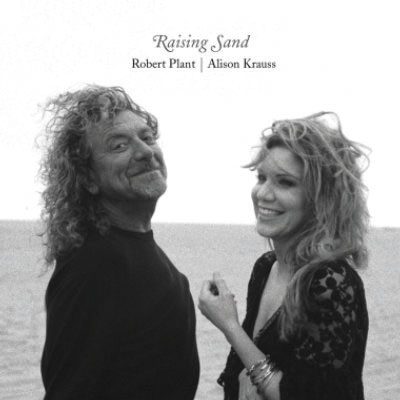

In those 18 years Krauss has contributed bluegrass tracks to the Coen brothers’ Hollywood hit O Brother, Where Art Thou (2000), appeared on stage at the Academy Awards, where she performed two nominated Appalachian songs from the movie Cold Mountain (2004), and recorded a successful rock/folk crossover album with Led Zeppelin icon Robert Plant (2007’s Raising Sand). So what was the thinking behind this career curveball?

“Every now and again, I’ll do a record without the band,” she answers matter-of-factly. “We all do it from time to time. I haven’t done one in a long while, but it didn’t feel weird at all. I don’t do anything that I’m not inspired to do.”

Nostalgic tribute

In this case, her inspiration came from the past – specifically her own past. Windy City is a gloriously nostalgic scrapbook of Krauss’s favourite country songs – 10 standards and rarities originally recorded by artists as diverse as Willie Nelson, Roger Miller, Eddy Arnold and The Osborne Brothers – all lovingly recrafted in her own inimitable style. “I wanted to sing songs that are older than I am,” she told Rolling Stone magazine in the build-up to the album’s release. “There’s a real romance in singing other people’s stories.”

It’s a brave yet brilliant record, and listening to Krauss’s hymnal longing on Brenda Lee’s All Alone Am I, or her tender vibrato on Glen Campbell’s Gentle On My Mind, it’s hard not to feel that Windy City is the LP she was always destined to make.

And yet, recording it was anything but a breeze. While sessions began in 2013, it was another four years before the album saw the light of day – Capitol finally releasing it in the US on Valentine’s weekend 2017, emerging in the UK three weeks later. The delay can be partly attributed to the singer’s extensive live commitment, with Union Station touring with Willie Nelson & Family during much of 2014/15.

Vocal barriers

But there was a more exasperating reason for the hold up: “I was having a lot of vocal problems,” Krauss coughs, as if to nail home the point. “It drove me out of my mind. Not because I was trying to get the record out as quickly as possible, but because having vocal problems when you’re a singer is a massive pain in the neck.”

Doctors diagnosed Krauss with dysphonia, a condition that can result in rough or harsh vocal qualities. With her confidence shot, she turned to renowned voice coach Ron Browning (who’d previously helped both Patti LaBelle and Wynonna Judd) to navigate her through the stormy waters.

Further guidance came from Nashville music legend Buddy Cannon, whom Krauss had first encountered while appearing on Jamey Johnson’s 2012 album Living For A Song: A Tribute To Hank Cochran – incidentally, Johnson returns the favour on Windy City, providing guest vocals on two tracks.

A veteran producer (Kenny Chesney, George Jones, Merle Haggard’s final album) and songwriter (George Strait, Billy Ray Cyrus, Don Williams), Cannon undoubtedly had the CV to preside over such a sensitive recording. But for Krauss, the man she fondly calls ‘Ears’ – due, she says, to his natural instinct for music – brought so much more to the studio than cold, hard experience. “Recording with Buddy was a lot of fun,” she remembers with a chuckle.

“[The vocal problems] were frustrating, and there were times when I couldn’t tell if the singing was going to sound bad until I got in there and heard it over the mic. But Buddy is a very funny guy; he has a really dry sense of humour. He’s also very calm and doesn’t get very excited. If he doesn’t like something, you’ll know he doesn’t like it, but he doesn’t get mad about it.”

Overcoming adversity

Not even the harshest of critics could describe Alison Krauss as a diva, but when you’ve been at the top of your game (and probably most other people’s games) for as long as she has, you could be forgiven for wanting to call your own shots from behind that glass screen.

After all, if you’ve got 27 Grammys on your mantelpiece, you shouldn’t have to take shit from anyone. However, rather than throw a tantrum if things didn’t go her own way during those stop-start recording sessions, the singer insists that she was more than willing to take Cannon’s hard-earned wisdom on board.

“When you work, you have your own kind of standards,” she admits. “But sometimes, a person will come along and you’ll say, ‘I’m going to hand over my standards to that person.’ That’s what it was like [with Buddy]. Without trying to sound cosmic or hocus-pocus, it’s just something you recognise; it’s something I recognised.”

Dream choice

There was another thing that Krauss took from Cannon during their collaboration, and it initially came as a surprise to the singer. “When we were looking for songs to include on the album, I told Buddy about this tune I remembered from my childhood,” she starts. “I said to him, ‘Jim & Jesse used to sing it live at some of the bluegrass festivals I went to as a girl, and I always found it such a sweet song. It was called Dream Of Me.’ Buddy’s eyes opened wide.

He was like, ‘Are you kidding me? I wrote that!’ Isn’t that wild? So we decided to do it, and Buddy and his daughter [Melonie Cannon, herself a recording artist] even sang it with me on the record. It was such a sweet moment.”

Interestingly, Krauss had originally intended to record Dream Of Me for her 1987 album, Too Late To Cry – her first long-player for Rounder Records – but Cannon for one is pleased that she decided to wait 30 years. “It was the easiest singing I’ve ever done,” he told The Tennessean in a recent interview. “I don’t know if that’s just because of hearing my voice blend with something as perfect as Alison’s, or what.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Dream Of Me isn’t the only song on the record that stems from one of Krauss’s childhood memories; indeed, the vast majority of the choices hark back to her adolescent days when, as a fledgling fiddle star, she attended local bluegrass festivals, sat glued to her parents’ television or played old vinyl records in search of musical inspiration.

One of those records, The Osborne Brothers and Mac Wiseman’s The Essential Bluegrass Collection, unearthed the jaunty It’s Goodbye And So Long To You, a song Krauss says she’d “always really wanted to record” and which she faithfully reproduces on her own album, with the help of Dan Tyminski and Hank Williams Jr on backing vocals.

The title track is another made famous by The Osborne Brothers, and features guest vocals from Jamey Johnson and Suzanne Cox. “The first time I heard that song was when I first met The Cox Family in Texas in 1987,” says Alison, referring to the group with whom she’s previously collaborated on both the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack and 1994 album I Know Who Holds Tomorrow. “It’s very close to my heart.”

Female perspective

The harmonic I Never Cared For You – featuring Suzanne Cox and her brother Sidney – sees Krauss channelling a non-charting Willie Nelson single from 1964, but “switching the lyrics around in my mind so that it sounds like a woman repeating something a man has said”. While Poison Love – a long-forgotten 1951 Bill Monroe B-side – secured its place on the tracklist because “it’s like the most excitingly rhythmic bluegrass tune, and I thought it would be really fun to do”.

And then there’s album closer You Don’t Know Me. Previously recorded by two male artists – originally by co-writer Eddy Arnold in 1951, and later by Ray Charles for his 1962 album Modern Sounds In Country And Western Music – it takes on a whole new meaning coming from a female voice. Or at least, that’s how Krauss interprets it.

“You Don’t Know Me is a little like [Bonnie Raitt and Richard Thompson’s] Dimming Of The Day, or [Linda Ronstadt’s] Long, Long Time, or that Gladys Knight & The Pips song If I Were Your Woman,” she says. “It sums up those times when a woman wishes she was saying something but never actually does; it’s a one-sided conversation that she never says.”

While Alison insists that the songs should not be seen as pitiful (“I love that there’s strength underneath there; that whatever those stories are, they didn’t destroy,” she says on her website), that sense of yearning pervades much of Windy City, and jovial interludes are few and far between (Krauss plays the fiddle on just one track). Of those melancholic picks, it’s probably the two originally recorded by Brenda Lee that carry the most resonance.

On the Manos Hadjidakis-penned All Alone Am I – which Krauss tells us she learned from watching the legendary American singer performing on a French TV show – she delivers a dewy-eyed vibrato over a lush orchestral arrangement that can’t fail to tear at the heartstrings.

The second of those compositions, Losing You, was written by Pierre Havet, Jean Renard and Carl Sigman, and originally recorded by Lee for her 1963 album Let Me Sing. Krauss seems proud of her take on the song, and she has every right to – not that everyone was convinced she could pull it off: “My son told me that he didn’t think I should do Losing You because he didn’t think there was any way to touch Brenda Lee,” she recalls with a laugh.

“He said she was so perfect that he was afraid I’d ruin the song. We would drive around town and he’d be like, ‘Mum, you’re so beautiful but you’ve lost your mind.’ Which was great because at the time he was only 14; I thought, ‘For him to know how awesome Brenda Lee was… I must have a pretty smart 14 year old!’”

25 minutes after our conversation started, Alison Krauss no longer seems fed up. The opportunity to wax lyrical about her favourite country tunes has given her a new lease of life, pushing away any frustrations she might’ve had about transatlantic phone lines, incoherent accents and that “pain in the neck” throat infection – for the time being at least. But ain’t that the beauty of the music we love? It has the power to heal you when you’re broken, to lift you when you’re down. And, in the case of Windy City, to blow you away.