Interview: Greg Graffin – Go Ahead Punk

With his love of folk evident on his latest solo album, punk spokesman Greg Graffin reveals the links between the genres.

It may not always be obvious, but punk rock and country music are closer cousins than first appearances would ever suggest. Forget the surface: the roughness, rips and snotty aggression on one side; the old-school, down-home familiarity on the other. Authenticity, passion, the basic premise that anyone can get involved and embrace their creativity, whatever their background; these are the foundations of both genres.

This is what gives them both their spark. It’s why Johnny Cash, the Man In Black, the outlaw’s outlaw, is seen by so many in both camps as the ultimate rock star. It’s why Willie Nelson crosses boundary lines with the slightest flick of his trademark plaits. It’s why Dolly Parton, with her laser wit, social conscience and fearsome intelligence, is roundly considered one of America’s greatest living badasses.

And while those people have been clasped to the studded bosom of many a moshpit warrior over the years, it goes both ways. Punk rock, after all, is now moving into middle age, the original angry young things of the late 70s turning into the respectable musical elders of the 21st century. It’s no wonder leading lights of the scene are looking further back to their roots and exploring music outside of their own career springboard.

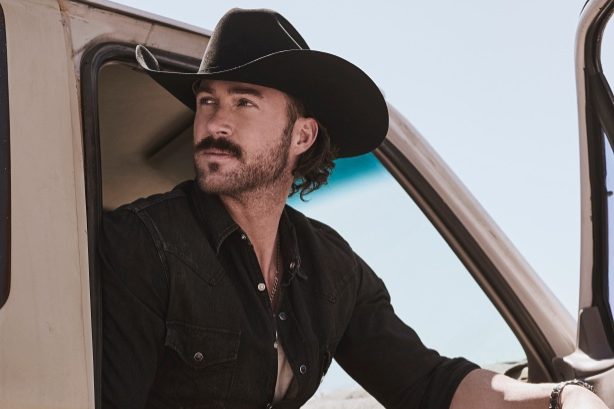

Take Greg Graffin, frontman of revered Californian punks Bad Religion since their inception in 1979. His new folk solo album, Millport, draws on the music he grew up with, the Grand Ol’ Opry songs his mother listened to on the radio when she was a child in Indiana: traditional Appalachian music infused with fiddle, banjo and guitar and a sense of deeply American tradition being handed down through the ages. It’s a beautiful thing.

“If it’s a good country song it still can be whittled down to an acoustic guitar and you can sing it around the campfire,” he says. “And believe it or not, it’s been our criteria in punk as well. Most of our songs are written on guitar or piano and then you take them in the studio and you adapt them to the genre. So consequently you can find me singing punk songs on acoustic guitar as easily as I do with folk music. As an artist is it feels very natural to play both of them.”

Bad Religion are the quintessential Californian punk band. Their lyrics take on themes of social responsibility and political discourse, but their harmonies are pure west-coast sunshine. But when we call Graffin, he’s holed up in his farm out east in upstate New York, looking out at a damp, dark, misty winter’s day. Millport is named after a nearby town, a real Anywheresville, USA, providing a strong home base for its rich metaphors for American life influenced by the likes of Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley.

“Some people say ‘well, that’s not what Greg’s really known for’, but the truth is I’ve been playing this sort of music since I was a kid,” Graffin says. “I now have three albums that are solo projects of my own, and I don’t get to make as many of these albums as I’d like to.

“People ask me how I learned to sing punk, and the truth is I didn’t, I learned how to sing this old-time music, this folk style, and if you blend that with rock, you’ve got something that just happened to be springing up in Southern California in the 70s when my family decided to move out there.

My vocal delivery has always been very authentic, I don’t try to sound like anyone. Early reviews for Bad Religion all said, ‘sounds like folk music’. And I didn’t really like being accused of being a folk singer, but the truth is that’s how I learned how to sing. I didn’t listen to Johnny Rotten.”

Integral Identity

Having grown up alongside peers such as Black Flag, Circle Jerks and The Adolescents, Bad Religion have gone on to influence everyone from Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder to Iron & Wine’s Sam Beam. Again, it all comes down to credibility and honesty.

“Everyone’s voice has a uniqueness,” says Graffin. “And so many singers try to disguise that uniqueness so they can sound like someone else. That turns me off right away. If I were ever on one of those shows that Simon Cowell hosts, I would be dismissed in the first round. And that’s true of every great singer that I know.”

The songs themselves combine a nostalgic mournfulness with a tongue-in-cheek humour.

While opener Backroads Of My Mind aches with a longing for home and roots, it’s also a self-mocking look at the physical and mental changes in an ageing singer. A take on Nashville songwriter Norman Blake’s Lincoln’s Funeral Train, meanwhile, looks to history to try and make sense of the seemingly unprecedented problems facing America.

“Lincoln’s one of our great heroes, but people forget his real impact internationally came after he was gone,” says Graffin. “His presidency was so tumultuous. If you think our country’s divided now, you should think of what it was when Lincoln took office.

“He had to sneak into Washington DC on a nighttime train and no one was told he was arriving, because there were lynch mobs waiting for him in Baltimore. He stole away to the White House from Springfield, Illinois avoiding cities where there were hostile people waiting to lynch him, literally. The country was never more divided and he presided over a terrible four years.

“This song commemorates his funeral train that went from Washington back to Springfield, and to me the image of a train is one of the great American images. It’s what connected this country and brought us into the modern era. I just think it’s a great reminder. During these current political struggles it’s good to remember how bad things got, remember how essentially we’re all connected.

I think that every time you travel around this country you see old rusted train tracks wherever you go.”

This emphasis on deep thought, on celebrating and embracing intelligence, has always been a hallmark of Bad Religion. Outside of the band and his solo work, Graffin is also writing a work of “speculative fiction” and works as an academic, with a PHD in Zoology specialising in Palaeontology, searching for the truth of natural history and evolution in the preservation of fossils. His traditional songwriting has taken a similar if swifter evolution since Bad Religion’s embryonic years, in the early 80s when they had just one album out.

“David Markey did a movie called Desperate Teenage Lovedolls. This was a movie about Southern California rock ’n’ roll culture. I did a song called Runnin’ Fast, and it was recorded as part of that soundtrack. That could have been added to my solo repertoire today, because it sounds just like the kind of music I’m doing now.”

Bad Religion are still very much a going concern.

They are not, Graffin says with no small amount of pride, a “heritage act”, relying on past glories and preaching to the converted. Instead, they’ve found that their audiences continue to bring in the young and the curious, kids looking for something to believe in, a home in punk rock.

“Heritage acts tend to be playing to older people who are reliving their childhood or their teen years through this music,” he explains. “For us, it’s still a living, breathing organism because we continue to add to our catalogue, young people continue to get involved and interested, and they come to the shows and they are just so excited to be able to see Bad Religion because, let’s face it, we’re an old band, who knows how many times we can continue to do this?

There’s still that excitement in the air, where they feel they’re going to witness something viable. And I think as soon as we stop being viable is when you stop touring.”

Band Of Brothers

Part of that punk ethos, of course, is brotherhood, of respecting and supporting the people around you. So it should come as no surprise that, for something billed as a solo album, Millport is a deeply collaborative project. It was co-written with and produced by Brett Gurewitz, Bad Religion guitarist and owner of the hugely respected independent record label Epitaph, while Graffin’s good friend of three decades, David Bragger, plays delicate and perfect fiddle and banjo on the record. “He grew up right next to me in California,” says Graffin. “So we’re kind of like brothers.”

The last piece of the punk rock puzzle is Jonny ‘Two Bags’ Wickersham, Social Distortion guitarist, Johnny Cash mega-fan and rockabilly nut. The two bands have an unbreakable fraternal bond.

“The strangest thing is Bad Religion and Social Distortion have such a long pedigree,” says Graffin. “Our first gig, in 1980, I was only 15 years old and we were opening for Social Distortion and they had only played three shows at that time. It took us almost 20 years of being colleagues and friends before we realised that we both have this common love of Americana music, and many of our influences are the same. It was really Brett who came up with putting them together with me. And sure enough they really loved the songs and when we got in the studio it was just magical.

“Maybe it’s because we have this parallel evolution, it felt like we’d been in the band together forever. I can’t describe how important that is when you’re in a studio pushing the record button, when the guys and you are almost like a family. It creates a magic on tape that you can’t describe.

That magic more often happens when you’re in the studio with your favourite people and your close associations. Maybe it’s because you lower your inhibitions, you’re more willing to take chances, and if it feels natural it’s more likely to come out on tape. And that’s exactly what it felt like for those ten days in the studio.”

Once Millport is released, Bad Religion are due to reconvene and start work putting the world to rights again, one perfect, razor-edged harmony at a time. There’ll be more solo songs from their tireless frontman, and once he’s got time he’ll be delving back into academia, making every second count. As Millport makes clear, time is a merciless hunter and it’ll catch you eventually. Graffin, for one, is wringing every last drop of nectar.

“Travelling is always a drag, but the concerts, at this stage are such a privilege I would never, ever have a bad thing to say,” he says, looking back on an inspirational career.

“I would thank everybody that ever comes to see me perform, that’s just a gift. Anyone who says that’s a drag is in the wrong business.” With a great brain constantly whirring and a creative impatience nagging to be fed, Graffin still has plenty left to give. So come together with him, country folk, punks, rockers and poets, because life is too short to regret not speaking your mind and your truth. And that truth can come out of the most unassuming little town, just like Millport.