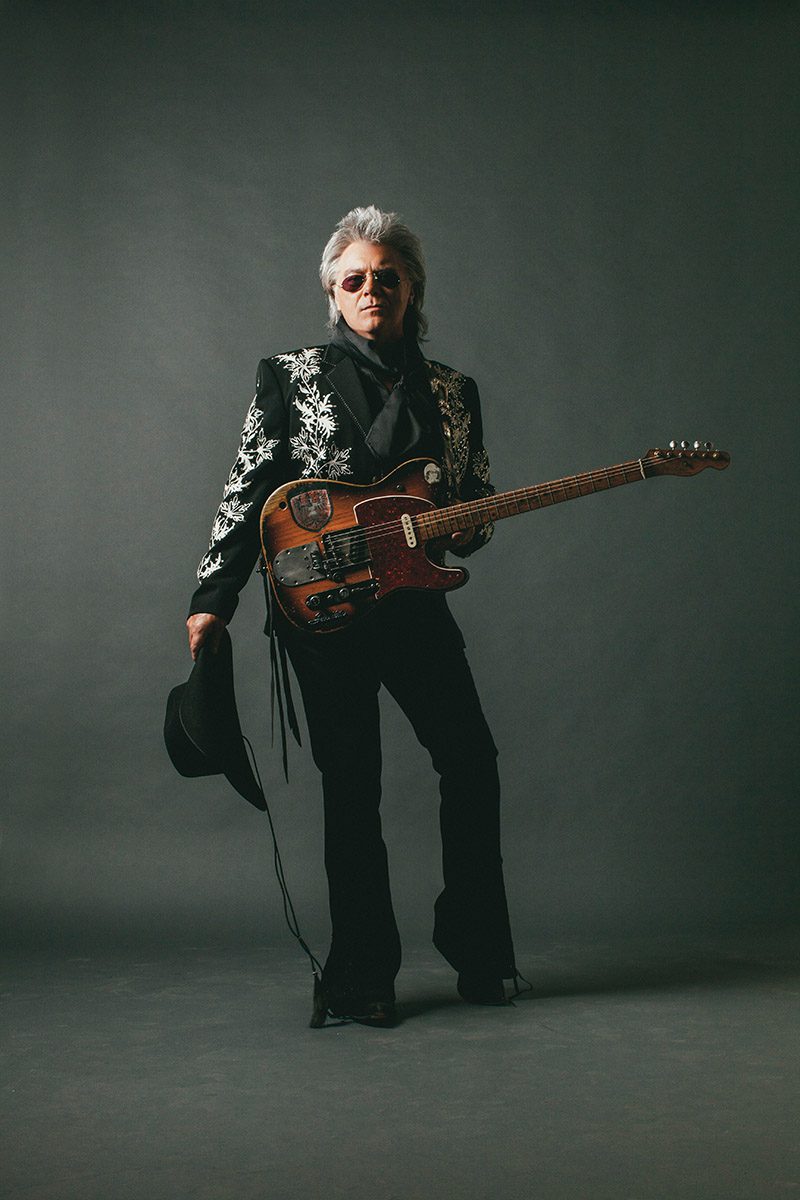

Interview: Marty Stuart & His Fabulous Superlatives

As he prepares to take to the stage at C2C, Marty Stuart looks back on his career touring with fellow icons Lester Flatt and Johnny Cash, and tells Ed Mitchell about his groundbreaking surf/psychedelia/country road trip record Way Out West.

It’s early February when we finally hook up with Marty Stuart. The four-week countdown to his appearance at Country 2 Country has begun and it won’t be long until his new album Way Out West bursts into life. The new record – a love letter to the American West, cut with his loyal band the Fabulous Superlatives – has already set the standard for the best record we’ll cherish this year. Yet, as this interview was taking place, the album was in limbo, recorded and mixed and out of Marty’s hands but still frustratingly far from delivery for the faithful who knew it was in the post.

“It’s like flirting with your favourite girl,” laughs Marty. We finish his sentence: ‘Yeah, you know you’re gonna get something good, eventually, and it’ll be worth the wait…’

We have to confess to a tingle of excitement when Marty Stuart picks up the phone. This is the man who toured with Lester Flatt and Johnny Cash and counted the likes of Merle Haggard and Porter Wagoner among his personal friends and collaborators.

He’s the keeper of the flame of true country music, a scholar and archivist and formidable singer, musician and writer. He even got to marry country royalty, the singer Connie Smith. If you want to know where country music has been or where it’s going, no one is better qualified to guide you than Marty Stuart.

While his new album testifies to his fascination with the West Coast, as he explains, his resolve to remain in Nashville was only tested once.

“In the late 1970s when Lester Flatt died, I considered going out West to live,” Marty recalls. “I was thinking about getting a job with Bob Dylan. At that time of my life, I saw the fast paced world of Hollywood. I thought, ‘you’ll probably go out there and kill yourself. You’re a knucklehead, Marty Stuart!’”

In the end, however, Nashville prevailed: “I got a job with Johnny Cash. That made an easy decision even easier.”

Q. Where does your fascination with the American West come from?

A. I was raised in the South of the United States, down in Mississippi. The first record I ever owned was a Johnny Cash record, it had Don’t Take Your Guns To Town on it.

There was another song on there called One More Ride, it was about going out West. Then, of course, I heard the Marty Robbins Gunfighter record. I was enchanted. Those songs took me on a journey in my bedroom when I was a little kid down in the South. To this day when I travel to the American West, I’m still awed by it.

Q. Do you remember the first time you made it to the West Coast?

A. It was 1974. I was in Lester Flatt’s band. He played a series of concerts; and the California show was in a town called Norco. It was a bluegrass festival. I woke up and we were coming into California and all of a sudden there were palm trees, there was a blue sky, and a ‘sandiness’ that I’d never experienced before.

I’d only read about it or seen it on the silver screen or on television. So, I finally got to see it in person. I fell in love with it the very first time.

Q. Way Out West feels like a soundtrack to a lost road movie…

A. I tried very hard to take the listener on a journey. I like themes. I like having a bullseye, a destination. It’s wonderful to know what the project is about. Therefore you can write to the subject matter.

Q. The title track is a powerful piece of work. When did the inspiration strike for the song?

A. I was riding in the front of my bus with a guitar in my lap and a piece of paper. These words just kinda started coming out of the sky. I thought it was comedy… like, this is crazy. I kept writing silly words. I actually wrote to sleep and when I woke up, I looked at the words again and thought, ‘well, that ain’t half bad.’

Q. You cut a couple of covers for the new record…

A. The second Johnny Cash record I owned was called The Sound Of Johnny Cash, on Columbia Records. Lost On The Desert was in there. I remember going down the street to my friend’s house and The Beatles were really popular at that moment in time. They were blowing up, lighting up the planet. He said, ‘Come here man, listen to this’ and it was a Beatles track. And I said, ‘Well, listen to this!’ and I played him Lost On The Desert.

I was just taken by that line in it: ‘black wings circle the sky’. Those images just captivated my mind when I was a kid. I thought Johnny Cash wrote that song but I found out it was Dallas Frazier and a guy named Buddy Mize.

Dallas Frazier is one of my friends – my wife Connie Smith has recorded like 73 of his songs. I called him up one day and asked if he remembered writing the song and he said, ‘Yeah, I think I was in high school when I wrote it.’ So it was one of those songs from my childhood that fit this project.

Q. You’ve got Airmail Special in there, too…

A. I love that line in it about ‘carrying mail to California.’ It was an old bluegrass record that I heard Jim and Jesse and The Virginia Boys do and I just thought it was a great song.

Q. Were the original songs plucked from the archives or written specifically for the record?

A. A little of both. A lot of the songs were written specifically for this record, but Old Mexico I wrote four or five years ago and I had hung onto it for the right time. So it was an ongoing process for probably five years.

Q. Way Out West doesn’t sound like a Nashville record…

A. We recorded it at Capitol Studios in Hollywood and at [Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers guitarist] Mike Campbell’s studio at his house. I thought it was a very California record. I knew if I made this record in Nashville – which I could have easily done – it wouldn’t have the right vibe.

Q. How does the atmosphere differ between Nashville and LA?

A. The first time I worked in a studio in California I scored this film called All The Pretty Horses. When I walked out the studio at night there were palm trees; there was that California atmosphere. Everything was different to Nashville.

Q. Why did you choose Mike Campbell to produce the record?

A. Mike is one of the finest musicians and producers I’ve ever known. He’s a great arranger. We first worked together on a Johnny Cash American Recordings album called Unchained. Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers, and myself, we were the band. Mike and I first hooked up when we played guitar on Rusty Cage. We’ve been friends ever since.

I just knew that I needed somebody from California, with a fresh perspective that didn’t worry about anything but making the music sound right. I took this concept to Campbell, played it for him and he seemed to like it. It worked out.

Q. For someone used to producing their own records, handing over control must have been difficult?

A. No, because I trusted him. When it’s right everybody knows it. You gotta get everybody to smile at the same time.

Q. How did the experience differ to self-producing 2010’s Ghost Train: The Studio B Sessions?

A. We had the luxury of more time. Studio B was another place that I wanted to bring some awareness to. Studio B is owned by the Country Music Hall Of Fame. Plus, Belmont University in Nashville has classes there.

So, we almost had to schedule our recording sessions between classes. At one point I looked out and we were part of the tourist attraction. But it was worth it for me to make that record there. Way Out West was a little more laid back. We didn’t have any eyes on us and we weren’t working off of somebody else’s clock.

Q. It comes across that the Fabulous Superlatives are a genuine band and not just a bunch of session guys backing a country superstar…

A. Oh, without question. That’s the beauty of the Fabulous Superlatives. Everybody is a star. You know, I was trained that way. When I was just a kid in Lester Flatt’s band, Lester made sure that everybody on that stage, or in the recording studio, had a say in the matter. Everybody was featured. When Lester passed away and I went to work for Johnny Cash, it was the same thing. John made sure it was an ensemble effort.

Q. Even by Nashville standards, the band are great…

A. From the first rehearsal, from the very first rehearsal, I knew that this was a special band. It wasn’t about chasing three-minute hits up and down Music Row anymore. This is much broader, much deeper, this is cultural. This was musical missionaries, or mercenaries, however you want to put it. I knew this was really about a ‘band’. Every night, my favourite thing to do is play rhythm guitar and sing baritone in the trio. I’m fine with that.

Q. You’ve long been regarded as Nashville’s keeper of the flame of real country. Do you feel a responsibility to preserve the heritage?

A. Well, it’s probably a self-imposed responsibility. It’s more about a love affair with that end of the culture. It’s a great mission to get up and go to work on every day.

Q. You’re actually the most ‘country’ of the artists playing at C2C. How do you feel about the stylistic shifts in modern country?

A. It doesn’t surprise me. Country music has always wanted to be a pop star. It’s about evolution. Country music has always been a bit of a reflection of American culture and there’s not a lot of country performers these days that were raised in the way that Merle Haggard, Bill Monroe or some of those old timers were.

Everybody is probably more suburban and they’re appealing more to suburban kids. I understand it, but that doesn’t mean the roots are less important. It means they’re more important now than ever before.

Q. Modern country has exploded in popularity…

A. There’s more people listening to what’s being termed country music than ever before. I mean, coliseums and stadiums are being filled with record numbers. I see country stars on the covers of the glamour magazines, mentioned in the same breath as Hollywood stars. I think, as far as that end of things, the culture is secure. The job from my perspective is to make sure we keep some authenticity in there or it just becomes disposable pop culture.

Q. The sad fact is, the kind of apprenticeship you served with Lester and Johnny just isn’t on the cards anymore…

A. I know, and I wish every young artist could have the same life that I did. There’s so much wisdom to draw from that I stored up along the way. I don’t care what the situation is, I can think back on a piece of advice or something that I saw and I can usually find my way through whatever the problem is.

Q. What were the important lessons you learned from working with Lester and Johnny?

A. I promise you whatever you felt like before you bought a ticket to come inside their show, after you left, you were inspired, you saw and heard things that made you think differently and walk a little faster and a little brighter. They were masterful entertainers in the way they could lift people beyond their problems, take them to the high road above their circumstances.

Q. What was it like joining Lester and Johnny’s bands for the first time? Were you a nervous wreck?

A. I felt like I’d found my home. I was only 13 when I joined Lester but I knew the moment I walked onstage that I was in the right place.

The first time I met Johnny he stood up to shake my hand. He kept looking at me and shaking my hand and he said, ‘Where are you from?’ I said, ‘Mississippi’.

He said, ‘I thought so. Where have you been?’ I said, ‘Getting ready, let’s go!’ Two weeks later, we were working together.

The strange part of this story and this is absolutely true, the first two records I owned were Johnny Cash and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. I studied those guys and I watched them from age five. I felt like I knew them. They felt like family to me before I even met them.

Q. Didn’t the same thing happen with your wife, Connie Smith?

A. Connie came to my home town to play at a fair. I was 12 years old and I told my momma, ‘I’m gonna marry her someday’. And I meant it. Lester, Johnny and Connie were the three principal factors. In. My. Life. I just felt like it was meant to be. I was dancing with destiny with all three of those people.

Q. Do you think Nashville is doing a good job promoting the music and preserving the past?

A. The reason Nashville succeeds beyond a lot of other cities is that it has a briefcase in one hand and a guitar case in the other. They understand the ‘business’ of the music. Whatever shape the industry is in, whatever shape the music’s in, I promise you there’s good business around. I have to applaud it for that. Sometimes it overshadows creativity but country music will always live on because they have a business model.

Q. Are you an artist that gets to make music on their own terms?

A. 15 years back, I thought you know what, I’ve done everything I set out to do. I have the girl of my dreams in my life. I’ve got some really cool-looking cowboy boots and the greatest Telecaster in the world. I’ve got a Cadillac that’s paid for and is really old, and 150 bucks in my pocket to put gas in it.

So, how about I stand for what I believe in and never forget the faith. So, the roots of country reappeared in my heart, and that’s where I have gone and stayed. You know, I’ve seen 40 years’ worth of people come and go around those roots… but the roots remain!