Shania Twain – Then & Now

Losing her husband and co-writer. Losing her voice. Fifteen years away. Can Shania Twain now reclaim her throne as the Queen of pop-country?

Shania Twain is back to prove she is still the one we want after a lengthy break from the music industry. It has been an epic 15 years since the biggest-selling female country artist of all time released the mega-selling Up!, but what has kept her? The answer is that Canadian queen of pop-country has been dealing with real life. Big, unpleasant dollops of it, like divorce, infectious disease and career-threatening vocal problems. She doesn’t want you to think she’s been ignoring for all this time us on purpose.

“I’ve been very busy raising my son [Eja, recently turned 16] and I’ve been very productive as well,” she says as she sits down to meet Country Music in the plush setting of an elegant London hotel.

“I just wasn’t productive in making an album project, because of my voice. So I never collected my writing. I was writing all the time, but I wasn’t writing for an album. So it took a little while to organise all of that.

“I wrote a book [the 2011 extraordinary autobiography From This Moment On], I did Vegas things for two years, and my voice did very well in a controlled environment. Then I did a tour, and that gave me more encouragement, then I built up to making the album.”

Getting back in the studio, she admits, was when push came to shove, “the most scary statement to make, vocally, because it’s so permanent.”

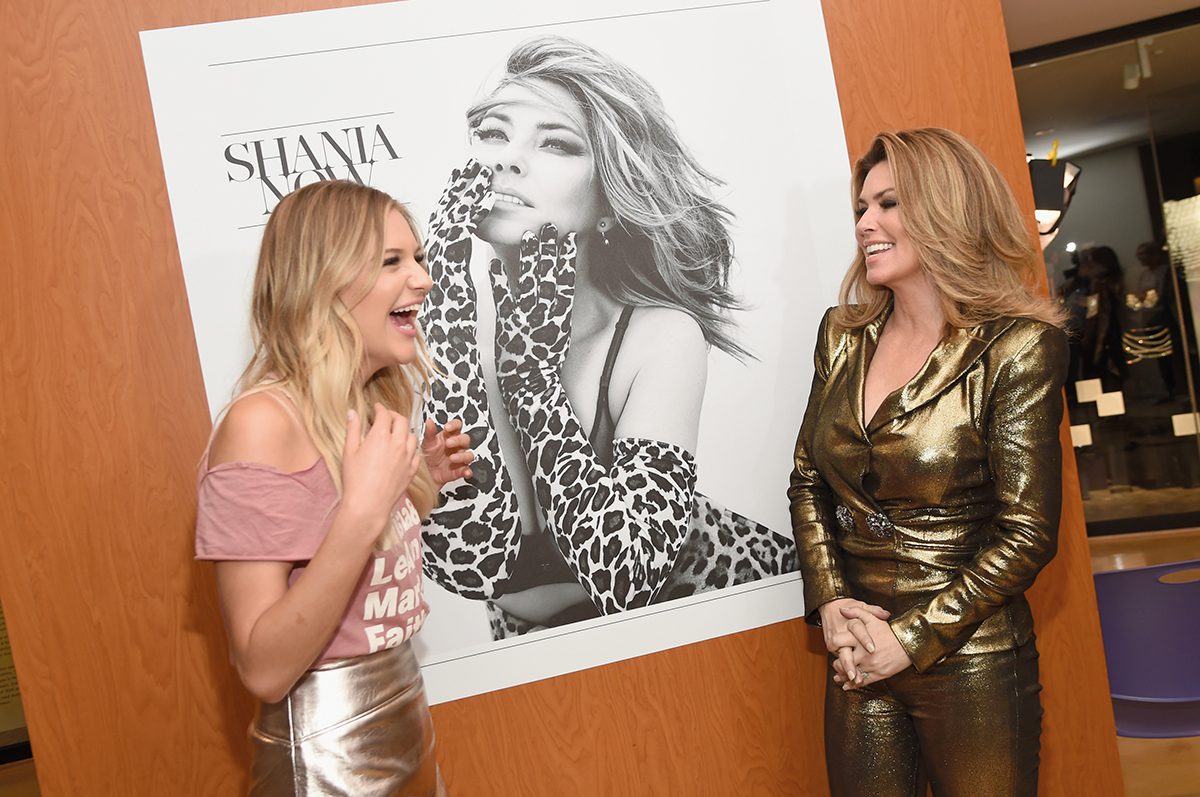

“It’s not like a live show, where it comes and goes,” she explains further, “once you put it out there, that’s it.” Twain is very much out there again with Now, a huge-sounding, hook-laden return to everything that ever made Shania sell by the multi-million in the first place. Its pop confections may reopen the time-honoured debate about how country she is.

But such semantics would have been way down the list of priorities when she decided, after recovering from Lyme’s disease and the loss of not just her voice but also of producer, co-writer and former muse ‘Mutt’ Lange, that she was going to write the whole thing on her own.

Remembering that painful period, she recalls: “Now I’m going to have to produce the whole project, because nobody knows me, and I wouldn’t even have known who to trust. Who would I write with? Would anybody want to write with me? I’d been quiet for so long, I just wasn’t sure where I would fit in that. So I thought, the more independent I can be with this, the better. It puts me to the test. And I committed myself to writing the whole album by myself.

“Once I got past that point of just getting started, it’s like going to the gym. The hardest part is getting there, right? Getting yourself dressed and out the door, and then once you’re there, it all starts happening. Of course it’s painful, you’re going to be sore the next day and go through some ups and downs. But you’ve taken that initial step. Once I dived in, I was committed, and then it really just got easier from there, to be honest.”

Twain and Lange split in 2008, after she discovered that he had been having an affair with her best friend, Marie-Anne Thiébaud. As if that wasn’t high-profile enough, she went on to marry Thiébaud’s estranged husband, Frédéric, and she knew the tabloids would be like pigs in the proverbial. “Of course!” she laughs heartily. “I thought to myself, well, there are just some things you can’t keep from the press. So on that hand I’m thinking, ‘The best thing to do is just get it out there so that they stop asking me things that they already know.’ Instead of leaving people digging, it was just so much easier to say yup, this is the way it is, and now there’s nothing to dig for.

“I’m not ashamed, I don’t need to apologise for what I’ve been through. It’s just what it is. I think transparency is sometimes just the best way to go. We all have the right to preserve our privacy without being called dishonest. That’s not a question of ‘true or false, it’s a question of: ‘Do I want to share that or not?’ There’s a level of transparency that I think does disarm a lot of unnecessary conversation, and it’s a relief for me.”

Now is an album in which Twain disarmingly lays bare her raw emotions, sometimes musing in the first person about how she can’t believe her longtime partner would leave her. But more often, she’s in pugnacious form, “swinging with her eyes closed” and later announcing, nay demanding, that “more fun is what we need.”

These are probably the most personal songs Twain has ever recorded, and there’s been something cathartic for her in laying things on the line. “I don’t just do it for entertainment, although we all love to be entertained and I want to be entertaining,” she says. “But I’m always just myself anyway. I’m not acting when I’m on stage. I’m singing my own truth, I’m not even interpreting. I’m not just presenting the song as the performer, I am the song and I’m extending my story by singing it to people.”

In any case, if you know anything about Twain’s upbringing, you know she’s been through worse than this. After her parents split when she was just two, she started to sing in nightclubs when she was just eight, to help the family’s threadbare finances.

“Those clubs were my performing arts school,” she laughs. “There was a detriment, because I developed stage fright there. I think it was just being forced into an environment that was so uncomfortable for an eight-year-old. It was very smoky in those days, I could barely breath, and it was dark and quite sinister.

Everybody was drunk, because I’m only going in there at midnight. I couldn’t go in before because they were still serving alcohol. So last call comes at five to midnight, whatever, but where I’m from at least, everybody [then] loads their table up with drinks and then they can’t make you leave. For that hour or so, that was my moment to get up on stage and do my set. So I would be playing to just totally wasted people.

“So that was my education as a kid, and I was tired and I often had school the next day. My mother would come, or one of my cousins who would sometimes play the guitar for me. From the age of 11, my parents weren’t always there, because by then I was legal. I could go in before midnight, the whole night.

“That was as bad. But I was never allowed to stay in the bar, I always had to go from the stage directly to the back of the stage. Then I went past the strippers on the way as they went to do their set! Trust me, by the time I got to Nashville, I was quite hard and ready for things.”

Far worse was to follow when her mother and stepfather were killed in a car accident when Twain was 22. Left with three younger siblings to look after, she was forced to move back to their home in Timmins, Ontario until they were old enough to take care of themselves, whereupon she started on the long road to Nashville. After what seemed an eternity, label interested reached a peak when Mercury Nashville signed her.

Let’s go girls, come on…

Shania’s self-titled 1993 debut album was only a modest success, and it featured only one song that she co-wrote, God Ain’t Gonna Getcha For That. But there was enough there to attract the attention of Lange, with whom she swiftly struck up a strong relationship, both professionally and personally. Their 1995 collaboration The Woman In Me set the template, with singles full of smart wordplays and adhesive melodies like Whose Bed Have Your Boots Been Under and If You’re Not In It For Love (I’m Outta Here).

The school of hard knocks from which she’d already graduated was about to prove its worth again, because many in the Nashville establishment looked askance at the newcomer. Country had been part of, but certainly not all of, her musical education. “Dolly Parton was in there, but I always considered her more of a folk artist when I was a kid,” she says.

“To me the more country artists that I was attracted to were Waylon Jennings, Kenny Rogers and Emmylou Harris, but she was folk to me. I loved that stuff. When I was recognising that I loved the song, I gravitated to more of the storytelling, harmony blend-type songs. Most definitely Carpenters songs, the Mamas and the Papas, Jim Croce, Gordon Lightfoot. I loved Bread, so underrated. Canada’s country was different, we had country and western. That would have been the Tammy Wynette, Kitty Wells and George Jones, and that was more my parents’ music. I was more Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.”

Nashville wasn’t necessarily convinced. She had the temerity to be Canadian and was already nearly 30 when she started to sell records in serious numbers with The Woman In Me and then on to the stratospheric success of Come On Over and Up!

“At the very beginning, when I first went to Nashville, I was totally the outsider,” she admits. “Well, I was the outsider, it’s not like I can even fault them with that. Culturally I had some adjustments to make, that was fair enough. Even at the time, I didn’t baulk at that. I wasn’t out to change anybody, I was out to be myself, and I had to have big enough shoulders to accept that being myself, not everybody was going to like who that was. I couldn’t expect everybody to like it, and I was ready for that. My childhood had prepared me for that.

“It was such a gift to have that strength, because I wasn’t rattled by the initial rejection. It almost gave me more strength, knowing that there was no turning back. It’s like: ‘Ok, I’m halfway across the river and there’s only one way to go, there’s nothing to go back to. I can’t turn around. If I’m going to drown, I might as well drown going that way’.So I think you swim better with that psyche. You’re going to go for it like you’ve never gone for it before, because surviving looks a lot better on the other side than it does going back where you started in the first place.”

Contrast that attitude with today. In June, the artist became the subject of Shania Twain: Rock This Country, a new, year-long exhibition at Nashville’s distinguished Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum that depicts that long route from abject poverty to worldwide superstardom. “When I go there these days, or I’m among other country artists, it’s a whole different world for me right now,” she beams. “I’m respected and welcomed there, and now I’m in the museum!” she says.

“I’m so honoured by it. I just feel really good about where I am right now, and that space in the museum represents that so well, that they’re honouring me in that way. It’s my life history, not just my career.”

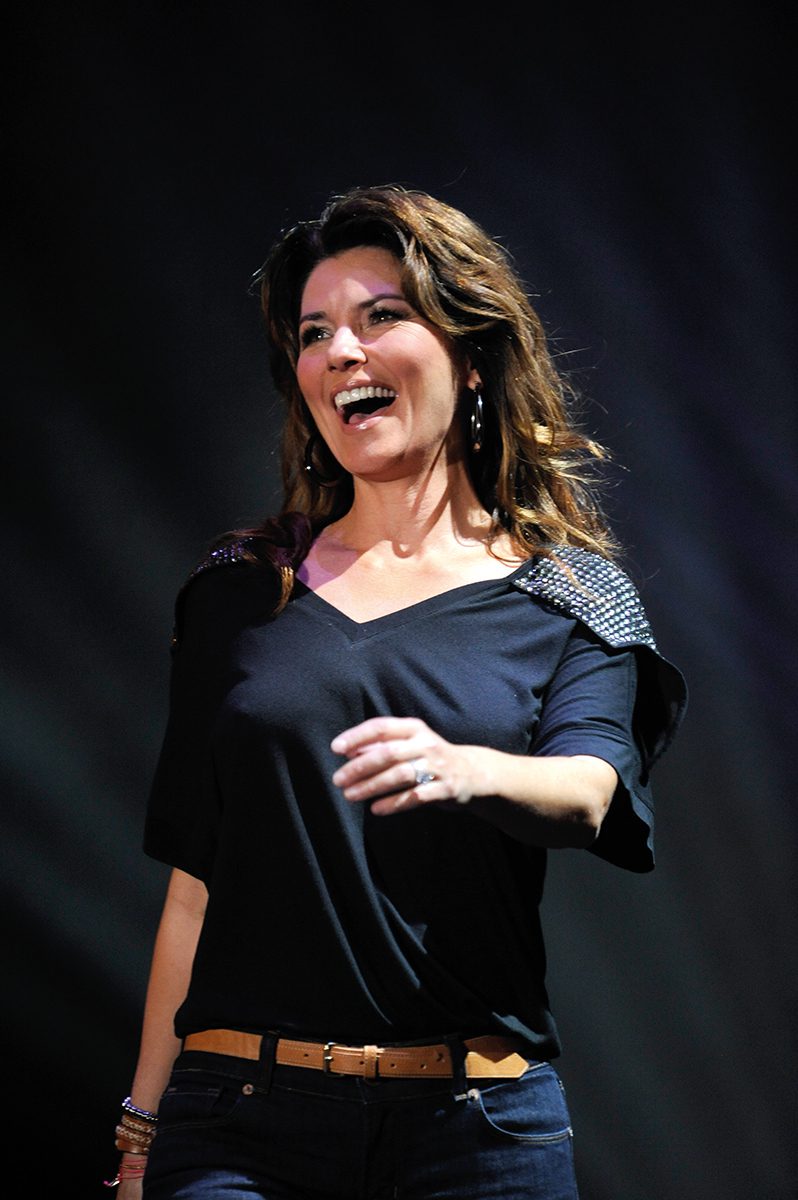

To underline that empathy, Twain’s first showcase for her new material was at the Stagecoach Festival, the annual country event in California, in the spring. “That was a lot of fun,” she says. “The crowd was amazing.” It’s the forerunner of more live work, which after her vocal issues, she will embrace enthusiastically, but carefully.

“If I prepare, I can do it,” she says. “The problem that I have is not endurance, as far as the physiological side, at all. It’s almost the opposite, I have to sing more in order for it to stay manageable. But it’s so physically exhausting. I’ve got to pace it differently, that’s what I learned. So I can stop and start as long as I don’t stop for too long, so that I don’t have to spend so much time building back up. I’ve got to pace it like an athlete, and I’ve got the luxury to do that now. I’m so excited about that.”

Shania Twain’s positivity may have had to survive some stern challenges, but ultimately she’s both reassured and re-energised.

“It’s so interesting what motivates you, and ambition is not one of those things,” she concludes. “That word is not really part of my intention in my career and in my life. This is not about career ambition, this is about surviving and going for it.”