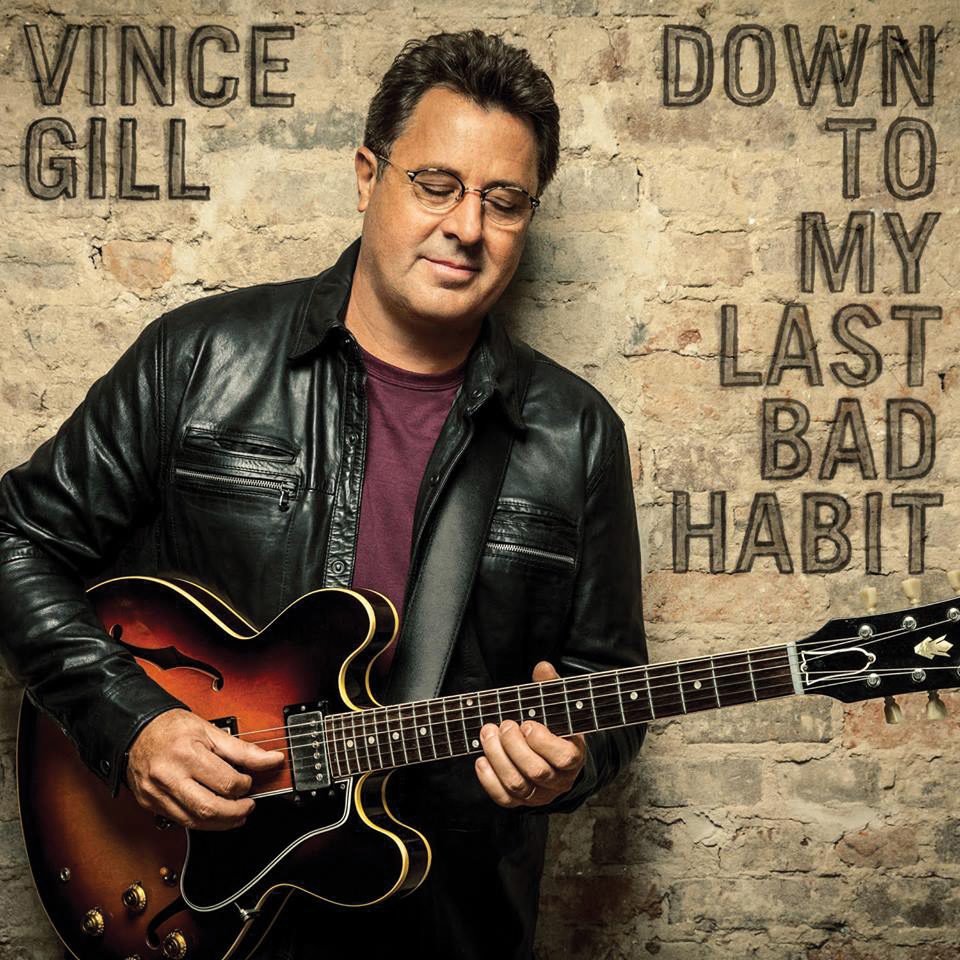

Interview: Vince Gill – The Mayor of Music City

20 grammys and countless hits later, Vince Gill is still at the top of his game, writes Paul Sexton.

On our way to Nashville’s hallowed Ryman Auditorium, we mention to a record-company person that we’re going to meet Vince Gill. “Ah yes,” they reply, with a warm smile. “The Mayor of Nashville.”

It may be an honorary title, but Music City has no greater ambassador than a 20-time Grammy winner genuinely loved and respected by everyone involved in the business, and many more besides. He’s one of those for whom no surname is required: it’s just Vince, country music’s close family friend, Nashville’s favourite adopted son for decades. Not bad for a bluegrass picker and Beatles fan from Norman, Oklahoma.

When we meet backstage at the famed venue, known to all as the Mother Church of Country Music, Gill is sitting alone in a small room strumming and studying potential tunes for an appearance at an all-star radio showcase. We tell him about his affectionate appellation.

“I haven’t been paid yet,” he laughs warmly. “But I love it here, I love to help out, I love to chip in and do my part, and I think I always have, ever since I’ve been here. I made my first trek here 42 years ago, and made one of my very first records here. So I’ve always been drawn to the city. I love the community of it, the spirit of it, the kindness of it. This place is surrounded with a lot of really kind people, and it makes you willing to want to help out.”

There was, he confides, at least one moment of doubt, very early on. “I moved here from Southern California, which is 75 and sunny every day. I showed up here and it was 17 below zero. It was freezing. ‘What have I done?’

“I didn’t move here until ’83,” Gill continues, “but I made a boatload of trips here to work on records, and work with other people and tour, so I had about eight good years of a lot of time in Nashville and always felt like I would wind up here. That opportunity was finally the right time to come, and I’m not going anywhere else, that’s for sure.”

All this time later, it was only right that, as the CMA Awards prepared to mark its 50th event last November, the all-star single Country Forever that marked the occasion featured Gill among its all-time greats, alongside Dolly Parton, Willie Nelson, Charley Pride, Ronnie Milsap, Randy Travis et al. As he prepares to turn 60 in April, Gill is a statesmanlike representative of the music and the city he adores. But his role is far more than that of a country figurehead.

He’s as deep in the trenches of recording, performance and collaboration as he always was, and his diary for last year was as packed as ever, with two album releases inside just seven months. His elegant, 14th album in his own name, Down To My Last Bad Habit, was followed in September by a delightful new endeavour with his part-time compadres The Time Jumpers, entitled Kid Sister.

Time traveller

2017 looks every bit as eventful. After finishing last year with his Christmas At The Ryman shows with his wife of nearly 17 years, Amy Grant, he’s swiftly back out on the road, and in March will reunite with his pal Lyle Lovett, for the third year running, on a nine-city US schedule. The humour, you can bet, will be bone dry.

On 12 February, Vince has a date at the 59th annual Grammy Awards, courtesy of not one but two nominations for that Time Jumpers set. As both an ever-active songwriter and a fervent traditionalist, both will have given him great satisfaction: Kid Sister is nominated for Best Americana Album, and its title track, his own composition, is up for the Best American Roots Song gong.

Down To My Last Bad Habit, I tell him, would be worth the price of admission for the title alone. He laughs. “The title track is a song I wrote with Big Al Anderson, who was part of a pretty legendary band here in the States called NRBQ, a lot of people’s favourite rock ’n’ roll band in history. “I got the title from a conversation at breakfast.

I was talking to a friend and said ‘What are you up to?’ and he said ‘Well, I’m doing alright, I’m down to about my last bad habit,’ and I said ‘Man! May I please have that? I want to write a song with that in it.’”

This was, by design, an album often displaying the crossover, soft-rock side to which Vince’s magnificent, mellifluous voice and dexterous guitar playing are so well suited. Indeed, four years before he made his debut in his own name with the Turn Me Loose record of 1984, Gill’s honeyed tones infiltrated the American pop Top 10, when he sang Let Me Love You Tonight, with his early band the Pure Prairie League.

“It’s fun for me,” he says of the solo album. “I don’t think it’s a very traditional country record for me, in that I did a record two years ago with Paul Franklin, the great steel player, called Bakersfield, where we played half Buck Owens songs and half Merle Haggard songs. Then when I play with The Time Jumpers, that really gives me the opportunity to invest in a lot of traditional country music – real twangy, the stuff I really love.

“So this record, I had a little more freedom to chase myself as a guitar player, and not try to have it be so steeped in that [tradition]. But there’s one on there that’s a real traditional country song I wrote for George Jones after he passed — another one of our great icons that should be on the Mount Rushmore of hillbilly singers.”

The song in question is the typically graceful album closer, Sad One Comin’ On, and it’s as sincere and heartfelt as Gill is himself. “It was just to honour him,” he says, “and his sweet wife Nancy for taking such great care of him over the years. He was a great friend and a great collaborator. I got to record with him plenty and tour with him.”

But the song, and the memory of it, bring out Gill’s reflective side. “When you start to see your heroes going to the other side, it has an impact, and it’s important that that comes out for me,” he says.

“When I struggle, that’s where I go: to a piece of paper, to write songs about things that I struggle with.” This is clearly a mindset that informs not just the album, but Gill’s entire raison d’être as he becomes what you might call a vigorous veteran. “I’m at that point in life where I say, ‘Okay, reality-check here, you don’t have as much time left as you’ve had to this point, so you’d better make it count.’

“So I feel like that losing my sweet buddy Dawn Sears, who sang with me for over 20 years on the road and on records. We were in The Time Jumpers, she passed.” Sears died of cancer in late 2014, at the age of just 53.

“I watched her go through that sickness,” says Gill, softly. “Every time, before bad health took her voice away from her, I knew she was singing like it might be the last time, and it was tremendously inspiring. So I feel like you’d better not leave anything in the bag, because you may not get another chance.”

An especially stirring performance comes on the track I Can’t Do This, written by Gill with new collaborators Catt Gravitt and Brennin Hunt. It’s a poignant tale of a lovelorn man who, as he sees his ex in a bar with another man, is “comin’ apart with each kiss”. She is wearing the dress he remembers, but still he torments himself. “Why do I watch this?” he asks himself. “He’s holding the one that I miss/ It’s like comin’ up on a car crash/ You look ’til you can’t take it anymore.”

“Oh, it’s tortured!” he laughs with me. “It’s one of the most compelling vocals I’ve ever done, in all these years of recording. There’s a tremendous amount of emotion in that song, and I think there’s a palpable emotion in my singing on this record.”

Gill Crush

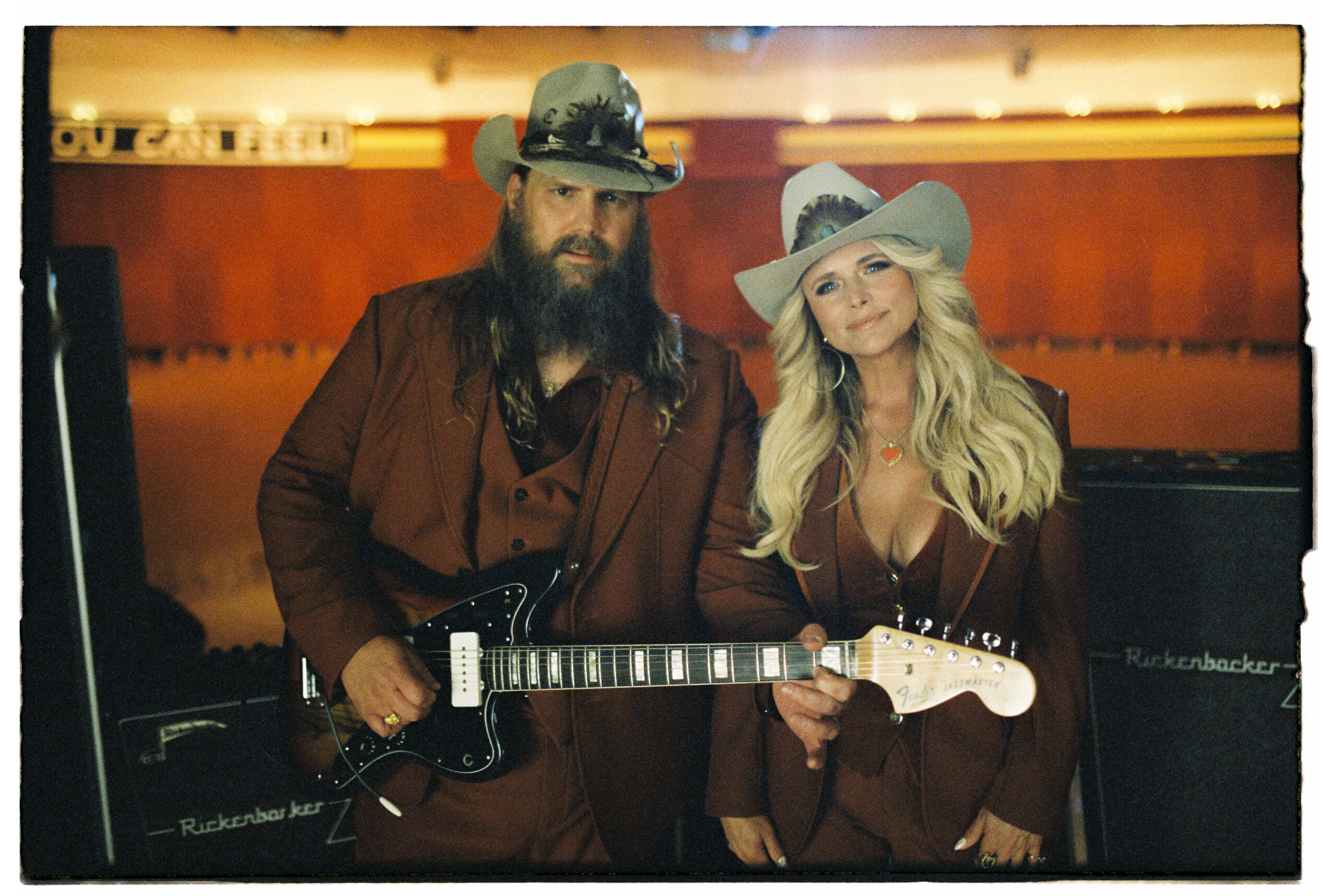

The album also features collaborations with Ashley Monroe, with whom Vince co-wrote My Favorite Movie; with Cam, the vivacious vocalist who sings I’ll Be Waiting For You with him and who will, without doubt, win a big new audience when she plays C2C 2017; and with current country trailblazers Little Big Town, on the single Take Me Down.

“I think it’s important to be willing to invest in young people,” says Gill. “To me, that’s always fun, to colour outside the lines a little bit and invest in the people you haven’t had the opportunity to do something with. That’s how I’ve always been pointed, always trying to find somebody to have that communication with.”

He warmly applauds the way Little Big Town have become poster boys and girls for not only the value of traditional songcraft, especially with their smash Girl Crush, but also how to take the genre forward, with wit, imagination and versatility. “I’ve been teasing them ever since they put it out,” he says, impishly. “I said, I’m going to do a parody of it, and it’s going to be called Merle Crush. They like that idea.”

Wordplay and storytelling remain at the heart of country music, and Gill loves to do both. “I remember all the years that I’ve done different kinds of television shows,” he muses. “They say, ‘Do you mind cutting out the last verse?’ and I say, ‘Sure, if you don’t want to find out how the song ends, that’d be great!’”

As he grew up learning guitar, banjo, dobro, fiddle, mandolin, you name it, Gill had an eclectic musical education, both inside and outside of country. “I was the youngest in my family, and I listened to the records of my parents and my big brother and my big sister, before I could develop my own playlist of what I wanted to buy and chase.

“I had a pretty good, diverse bunch of music to draw off, so I have a reverence for the generations before me and a healthy respect for those folks, [especially] getting to meet some of those folks who were the real pioneers and the patriarchs of this music.”

He was steeped in Merle, and Patsy, and Ray Price, but also – being seven when the British Invasion landed – in The Beatles and the Stones. Always, above everything, came an appreciation of the craftsmanship that went into the art, and not just by the headliner. “When you’ve lived a good bit of life, you’re most drawn to what impacted you early on,” he says. “That seems to resonate to me. The new stuff is great, and every now and then, I’ll hear something I’m really crazy about.

“But the muscle memory of your past is amazing, what it makes you think of. I’ll hear Yesterday, or something like that, and it’ll take me back to the first dance with a girl when I was a kid. I remember trying to learn to play that song on guitar. It’s pretty neat.

“It’s musicians that create those brain tracks. You hear the intro to Patsy Cline’s Crazy and you know, in three notes, it’s Crazy. Not because Patsy sang it, but because of what a musician played long before the song starts. Those are the things that create that familiarity, and the defining moments of a lot of great records was because of what some great musician played.”

Play it forward

Now, it feels as though Gill and his close buddy Marty Stuart (mouthwateringly, another impending C2C visitor) have become historians who are part of the history. “Marty and I have been friends since we were teenagers,” says Vince. “People would always say Marty was born in the wrong era. I said, ‘No, he’s in the perfect era,’ because he has the opportunity to teach it forward. So I think it’s good there’s folks like Marty and myself that have a healthy reverence and knowledge of it.”

Gill talks approvingly of the palpable upswing of country music both in the US and on this side of the Atlantic. He’s also pretty sanguine about its embrace, in the hands of such current stars as Sam Hunt, of hip-hop.

“I wouldn’t know how to do it, it’s not part of my history,” he says. “But it’s what I tell people all the time, who don’t enjoy what’s going on with current styles of music. I say, ‘Look, we’re the age we are, we didn’t have this growing up. All the young kids have a huge hip-hop stretch of their growing-up years, so it makes sense that it’s filtered into our music a little bit.’”

Country, he agrees, continues to evolve. “It started in the 20s, on record with Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family. Those were the first records made, and you had one that was steeped in the church, and one that was steeped in the Depression and hard times and the blues. So therein lies the great diversity, and it’s always zipped around and been whatever, and changed and come back. It’s the way it’s supposed to be.”

We talk about the ups and downs in country’s vital signs in the UK, where he applauds the massive explosion of interest and credibility of recent times. “Truthfully, it’s the same here,” he says.

“It goes through periods where it’s not the go-to thing, and periods where it’s the only thing. I was fortunate that my era of success was maybe its biggest in history. But it’s like all things are new and different in a sense, because of the way we communicate and connect with people and what we can do with this whole world of computers.”

Vince Gill isn’t ready to become the grand old man of country for a long time yet. But he’s amassed the kind of experience and wisdom that few ever get to stick around to share. “If people ever ask advice, which isn’t very often,” he reflects, “I say look, if you want to have a career in music, you have to go somewhere, whether it’s California, New York City, Nashville, where there’s that community.

“It’s not going to come and pluck you out of Des Moines, Iowa, and make you a star,” he says. “You have to be willing to put your nose on the pavement and struggle.”